During the time of Jesus, a ruler by the name of Herod engaged in what was described as infanticide of male hebrews. Ron Brown (Fmr. Secretary of Commerce), Tupac Shakur, Mickey Leland, El Hajj Malik Shabazz, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Marcus Garvey and Huey Newton are a number of Black men silenced for whatever reason.

What

will this become, yet another conspiracy theory? Or will society come

to grips with this disturbing trend? Another variable within this

equation revolves around the high incarceration and death rate of Black

men. How can a scholar or African leader live with the destruction of

hope? There also remains the short list of Black men hemmed up over

trumped up charges and imprisoned because of it. If only we could see into

the past, maybe the future. What would we do? Maybe adjust flaws of

character, and bring back Moses? Are any of these acts or actions

related? What measures will some take to keep power out of the hands of

Africans? Geo-political destabilization of Africa and America may

benefit a white supremacist ideal; our old friend divide and conquer

rears its ugly head. The aforementioned issues suggest fault--I ask

candidly, who is to blame? There is a belief that certain elements

within American society are administering policies which seek to destroy

or destabilize the American Black male.

What

will this become, yet another conspiracy theory? Or will society come

to grips with this disturbing trend? Another variable within this

equation revolves around the high incarceration and death rate of Black

men. How can a scholar or African leader live with the destruction of

hope? There also remains the short list of Black men hemmed up over

trumped up charges and imprisoned because of it. If only we could see into

the past, maybe the future. What would we do? Maybe adjust flaws of

character, and bring back Moses? Are any of these acts or actions

related? What measures will some take to keep power out of the hands of

Africans? Geo-political destabilization of Africa and America may

benefit a white supremacist ideal; our old friend divide and conquer

rears its ugly head. The aforementioned issues suggest fault--I ask

candidly, who is to blame? There is a belief that certain elements

within American society are administering policies which seek to destroy

or destabilize the American Black male.Young Blackmen are not being nurtured to hold power. So similar are the tactics of Herod, attuned with the shadowy enemy of a would-be messiah. Is there a direct correlation between a male leader of African descent, and an effort to work towards his demise? In college, some taught the varying aspects of logic, be it deductive or inductive. Why not borrow from this concept, and begin to look further in what has been suggested. Maybe it's a coincidence that so many Black male leaders have been assualted. W.E. B. Dubois spent his mature years in Accra, Ghana. Dubois may have washed his hands of society's treatment of individuals of African descent. Hopefuly life for young Black men can be productive and prosperous so long as King Herod doesn't get a hold of them. Our current leaders have yet to devise a plan which embraces the young Black male, in an apprentice like posture, preparing them for leadership. So many questions, so few answers--our faith shall respond to all.

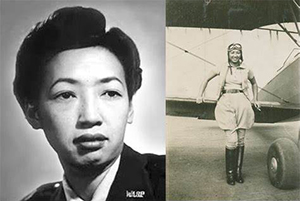

Born and raised in Portland, Oregon, Hazel Ying Lee became the first Chinese American woman to earn a pilot’s license and fly for the U.S. military under the Army Air Corps.

Born and raised in Portland, Oregon, Hazel Ying Lee became the first Chinese American woman to earn a pilot’s license and fly for the U.S. military under the Army Air Corps.